WHERE ARE MULTIPLE UNIVERSES?

We have all wondered how different decisions could change our lives, and as long as we are alive, these thoughts will never leave us. We can speculate about how much our lives might have changed if we had implemented a decision we didn't, but we can never know what might have been. Still, have you ever imagined that these different scenarios might have played out somewhere in other worlds?

While seeking answers to such questions, researchers are also trying to understand what kind of universe we live in. In order to find a positive answer to the question we asked earlier, they pursued the multiverse theory, which posits that ours is just a small bubble and in the other bubles other options also exist. For most of us, this evokes parallel realities that are not very different from ours but show slight differences. For example, in one universe, we have joined our lives with a person named A, while in another, we have joined our lives with a person named B, and our reality has changed accordingly. The “many-worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics has made this type of multiverse model more popular.

The ‘Many-Worlds’ interpretation of Quantum Mechanics is a strange but highly successful model of how the universe operates at the smallest scales. In this model, every possible quantum state creates a new universe. In other words, every physically possible action, every possible choice, is happening somewhere. Such parallel universes may exist, and evidence suggesting this ‘many-worlds’ interpretation of quantum mechanics may one day be found, but they can never be observed because they are separated from our universe in ways we can scarcely comprehend.

Cosmologists like Matthew Kleban are instead interested in a macrocosmic multiverse that we can grasp in more concrete terms; something beyond our current universe, but still something we can learn about. Kleban, a physics professor at New York University and one of the leading multiverse theorists, says: "In cosmology, we have a horizon very similar to the horizon on Earth. If you are on an island in the ocean and you climb to the highest point, you realize there is a finite distance you can see. You cannot see or know what lies beyond that horizon with optical means. However, you can still learn about it; like a log with some plants growing on it floating towards your island. You can learn things from beyond the horizon because various signals can reach you from beyond the horizon."

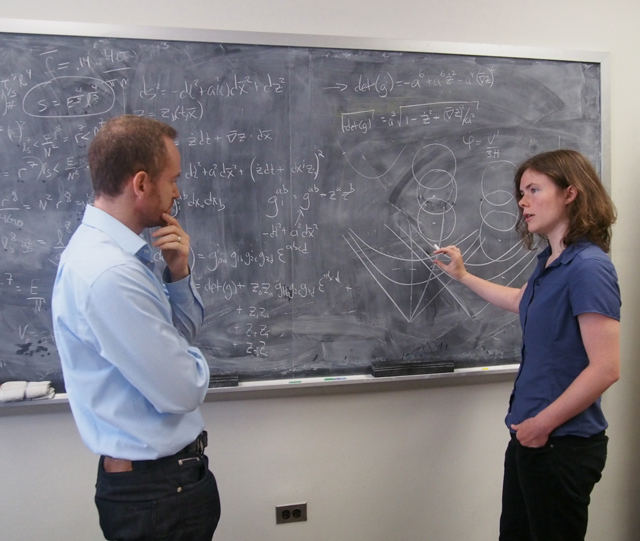

Matthew Kleban, an associate professor of physics at New York University, and graduate student Marjorie Schillo discuss what would happen if two bubble universes collided.

Of course, when it comes to our Universe, we must consider that this horizon is much farther away than the horizon on Earth, potentially about 46.5 billion light-years away in every direction. The reason this visible edge of the universe is invisible to us is due to the finite speed of light and the fact that the universe has been rapidly expanding since the Big Bang. According to the best current measurements, the Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago, and therefore we can only see objects whose light has had time to reach us, traveling at a speed of 299,792 kilometers per second.

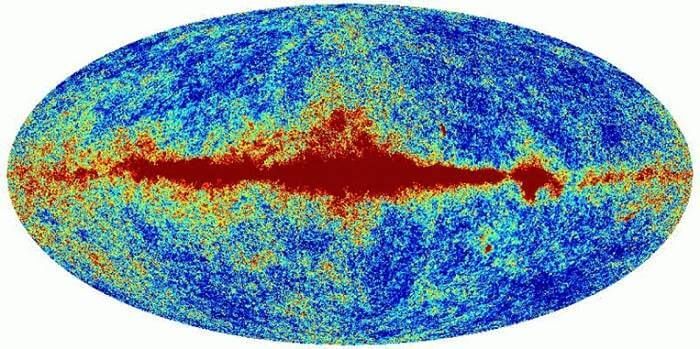

Because the early universe was extremely dense, the first light only formed 380,000 years later. This light, which transformed into invisible microwave radiation during its long journey through the expanding space, is the farthest thing we can directly observe. This cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation plays a key role in the search for evidence of a multiverse.

Matthew Kleban, an associate professor of physics at New York University, and graduate student Marjorie Schillo discuss what would happen if two bubble universes collided.

Of course, when it comes to our Universe, we must consider that this horizon is much farther away than the horizon on Earth, potentially about 46.5 billion light-years away in every direction. The reason this visible edge of the universe is invisible to us is due to the finite speed of light and the fact that the universe has been rapidly expanding since the Big Bang. According to the best current measurements, the Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago, and therefore we can only see objects whose light has had time to reach us, traveling at a speed of 299,792 kilometers per second.

Because the early universe was extremely dense, the first light only formed 380,000 years later. This light, which transformed into invisible microwave radiation during its long journey through the expanding space, is the farthest thing we can directly observe. This cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation plays a key role in the search for evidence of a multiverse.

Kleban continues, "We don't know what lies beyond the horizon, but what we can do is make predictions based on what we can see. On these large scales, the universe is almost homogeneous and isotropic, meaning it is almost the same in every direction. It is certain that the universe is much larger than what we can see, but this is not particularly interesting; it is a fundamental assumption of modern cosmology, known as the cosmological principle."

image; Cosmic Microwave Background radiation

It is an intriguing question how far the unseen parts of these distant points in space-time extend. Naturally, the answer to this question depends on the shape of space. This distance varies from approximately 250 times the observable universe for a closed and finite universe where space is curved inward like a sphere, to infinite dimensions for a flat or open universe where space is curved outward like a saddle. No matter how vast space is, we would expect some parts of this vast universe to be fundamentally similar to ours. If the universe is truly infinite or nearly infinite, we could expect parts of it far away from us to be identical to our observable universe.

How far away could these parallel universes and our copies living within them be? Our observable universe, with a radius of 46.5 billion light-years, has enough space for 10⁸⁰ particles. Try to imagine all the different ways these particles could be arranged: mathematics tells us that there are 2 to the power of 10⁸⁰ different arrangements of all these particles, meaning we would have to travel 10 to the power of 10⁸⁰ meters (an unimaginably large number) before encountering another copy universe with copies of ourselves living parallel existences. That is a very long way. By comparison, our observable universe is 8.8 x 10²⁶ meters wide. All we have described so far is limited to physically traveling to another universe and seeing it through conventional means. If the universe is infinitely large, then there is sufficient space for the specific arrangement of particles that make up our universe to be repeated countless times.

What if there is another type of multiverse? For example, a universe where universes emerge like bubbles and have the potential to be radically different from ours? This intriguing possibility, which fascinates Kleban and many of his colleagues, is based on a concept called eternal inflation. "In everyday life, we are familiar with the states of matter; for example, we know that a water molecule can be liquid water, ice, or steam. However, in fundamental physics, it is not only matter that has different states, but everything around us, space and time itself. Theories such as string theory predict many different states that are much more different than the difference between ice and water. Such universes would have different physical laws than the ones we know. For example, fundamental particles of the cosmos, such as electrons and quarks, might not exist here (in another phase). They could have a different form or different properties, such as electric charge and mass. These different phases are a general feature of many modern cosmological theories."

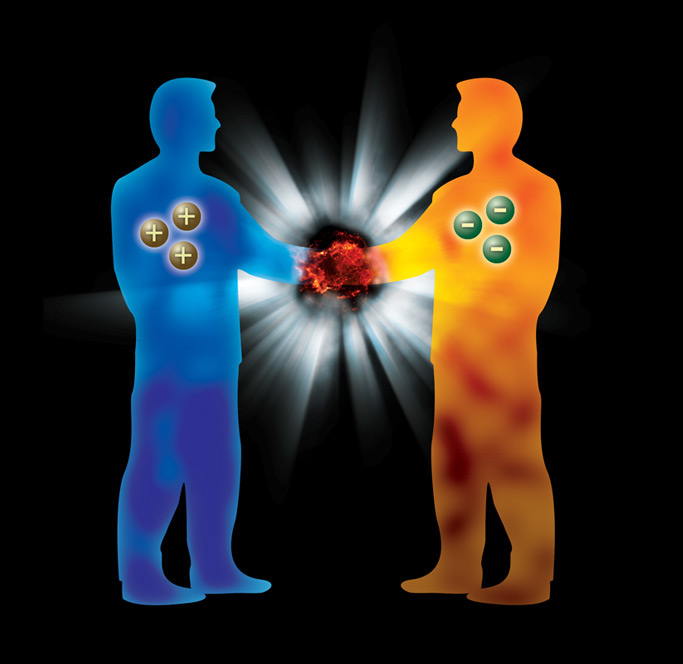

Among the various properties that could change from one phase (universe) to another is the strength of the vacuum energy permeating empty space. Over the past decade, strong evidence has been discovered that a small amount of this phenomenon, known as dark energy in our universe, accelerates the expansion of the cosmos. However, in other phases, this energy may not exist at all, it may be much stronger, or it may even have a negative value. Apparently, this could be the key to creating new universes in such a multiverse. If all these different phases can exist, then there must be transitions between them (as there are between ice, water, and steam).

Kleban explains it this way:

"You could have a universe that starts out with a single phase everywhere, but bubbles in different phases will inevitably appear randomly, like bubbles in champagne. Whether a particular phase has positive or negative vacuum energy is a kind of coin toss. But even in that case, at least some will be positive. If the vacuum energy is large, the bubble expands exponentially, doubling in a fraction of a second, then doubling again, and so on. The volume will suddenly expand in these regions. If these phases are unstable, then bubbles will appear within them; this is what we call infinite inflation.“ As Kleban admits, this is quite a mind-opening concept: ”If all this is true, we could be inside one of these bubbles, and outside there is probably something extremely exotic, most likely rapidly inflating and subject to different laws of physics, perhaps even a different number of dimensions. When you cross the wall of our bubble, the multiverse is anything but boring and isotropic."

Infinite inflation could explain one of the greatest mysteries about our cosmos. The properties of the universe seem finely tuned for life. If the gravitational constant were slightly stronger, an electron's charge slightly smaller, or the force binding particles together slightly weaker, stars and planets couldn't form; we wouldn't be here. Everything is just right, like Goldilocks' porridge, and so far no one has been able to explain why. However, if there are an infinite number of bubble universes, each with slightly different properties, then there must be one universe (ours) where the properties are exactly right, and this explains why we exist.

One of the biggest questions is: How can we find evidence that will either confirm the theory or prove that such a thing is impossible? The idea that the multiverse theory cannot be proven or disproven has been a common criticism among skeptics. This is also an area on which Kleban has focused much of his work and research. "The nice thing about the theory is that it also has observational consequences. If other bubbles form close enough to us, then they could collide with our own bubble. It's very difficult to detect these consequences with our current technology, but it's not impossible. At least we know what we would see and therefore what to look for,“ explains Kleban. ”The theory makes predictions that are both testable and falsifiable. It predicts that our bubble must have an open spatial geometry. If we measure the geometry of our universe and find it to be closed, then that would falsify everything."

So what traces might a collision with another bubble leave on our universe? As you might imagine, a collision between two universes is a highly energetic event. “The walls of these bubbles are extremely rigid and move at speeds very close to the speed of light because there is a force driving their expansion,” Kleban notes excitedly. "The bubble naturally wants to expand and consume the vacuum energy around it. This converts into kinetic energy in the wall, so they collide at high speed. The result is a wave of energy injected into our own bubble. This wave spreads throughout our universe in a phenomenon we call the ‘cosmic awakening’. Everything is affected by such a situation, but most importantly, the cosmic microwave background radiation. This is what we want to look at; because this is the oldest and most distant light, and therefore has had the most time to be affected by such an event."

According to most simulations, a collision between universes would appear as a ring of slightly higher temperature in the normally random distribution of the CMB (Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation) and light with different polarization (waves aligned in a specific direction instead of randomly arranged waves).

"So far, we haven't found strong evidence for such collisions, but there are some anomalies in the KMA that resemble bubble collisions. I don't take them very seriously, but imagine there really is something there at the threshold of detectability. This thing would produce an anomaly of marginal significance. We are expecting new and important data from Planck in the form of a polarization map covering the entire sky. This is a piece of data that is partially independent of the temperature maps. Certain types of bubble collisions will leave a very distinct mark on the polarization."

If our universe turns out to be just one of an infinite number of universes in a multiverse, the implications for cosmology will be enormous. We will no longer think of space and time as having emerged in a single event 13.8 billion years ago; that will merely mark the point at which our universe came into existence and began expanding. However, as Kleban also points out, our potential multiverse research is still in its infancy: "We are focusing on certain types of collisions because these seem to be the ones we have the best chance of observing. But there may be things we are missing. Another possibility is a completely different type of observation that we haven't yet been able to make or even conceive of. The important thing is that detecting the multiverse is possible. When something is possible, we can discover a sensible way to do it. We are still at the very beginning."

Levent Aslan

Add Comment