WHY IS THE BHOPAL DISASTER NOT AS WELL KNOWN AS CHERNOBYL?

If I asked you, what is the greatest industrial disaster to have befallen humanity? I am absolutely certain that almost everyone over the age of 50 today would say the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Accident. Because the Chernobyl Disaster of April 26, 1986, was the accident that was most frequently covered in documentaries, books, newspapers, and magazines. So much so that it was somewhat exaggerated, going beyond emphasizing the dangers that could occur in industry and reaching the stage of profiting from this human tragedy.

Now, if I asked you if you remember another disaster? Those who think a little more carefully and remember the recent past would also add the Fukushima disaster on March 11, 2011, to this list of disasters. A tsunami following a magnitude 9 earthquake in Japan destroyed the nuclear power plant's seawall and flooded the plant. The seawater swept everything in its path, causing partial overheating in the reactors, which led to meltdowns and explosions.

Let me briefly explain the picture that forms in your mind. One, Russia, or any Eastern Bloc country, cannot do anything properly. Two, if even the nuclear power plant built by the Japanese got out of control, nuclear power plants are the most dangerous industrial structures.

Is the actual situation as it forms in our minds, or is someone interfering with our thoughts? For example, there is only one case in Fukushima where death from radiation has not been clearly proven. A person who died of lung cancer four years later. In Chernobyl, 30 people died initially due to the explosion. The number of deaths caused by the effects of scattered radiation is quite controversial, ranging from 4,000 to 30,000. In Fukushima, during the evacuation of around 160,000 people, there were about 50 deaths due to stress and fear, not caused by the reactor accident.

These were not nuclear bomb explosions. The number of deaths recorded at the moment of the explosion cannot even be compared to the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. So what was it that drew the world's attention to these accidents?

Let's now focus on a disaster created by a multinational company whose name you have probably never heard of.

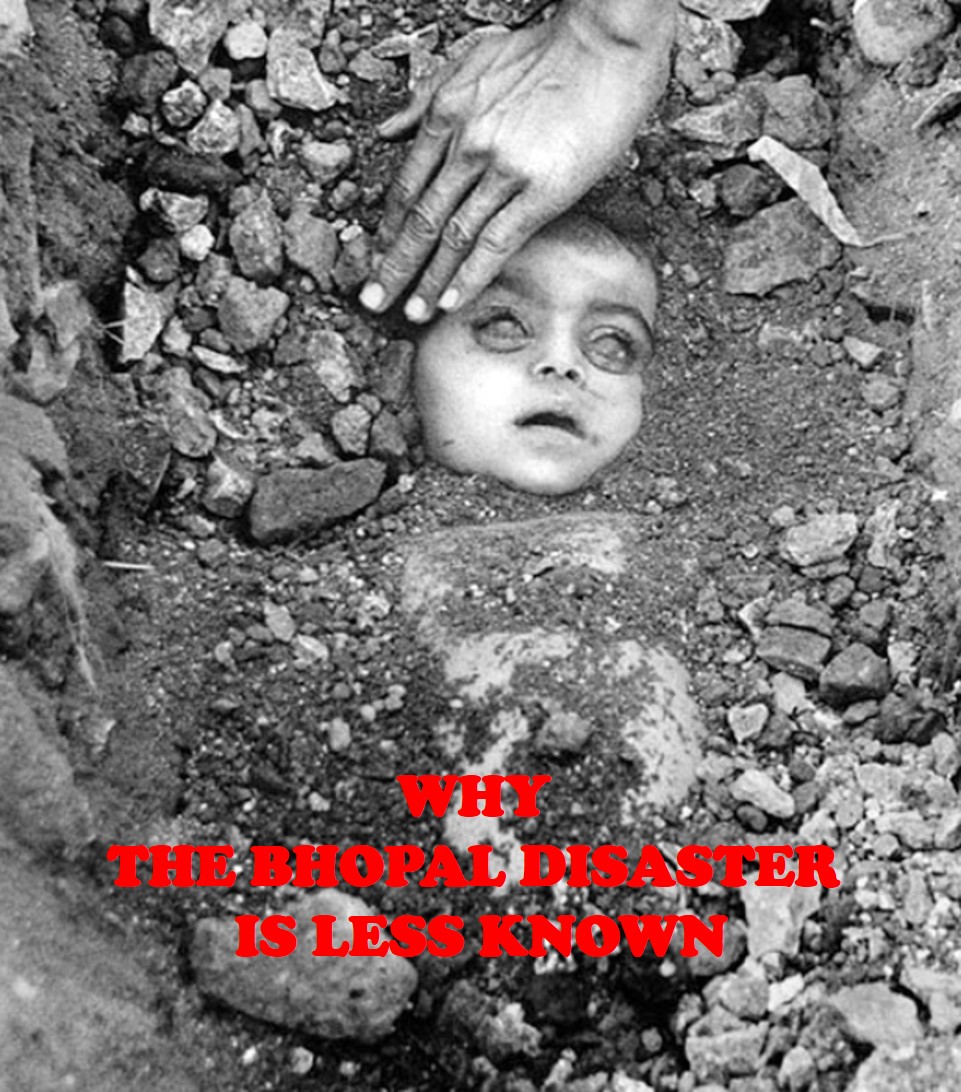

The date was December 3, 1984. The location was Bhopal, India. In the first moments of the explosion, 2,259 people lost their lives. I am writing this down immediately so that you can easily compare it with the figures above. In the days that followed, the death toll rose to 3,787. A total of 25,000 people were reported dead. Would you like to guess the number of injured? Exactly 574,000 people. Today, around 120,000 people are living with the damage this accident left on them or dying because of it.

Unlike Chernobyl, the Bhopal disaster has been covered in only six books and four documentaries. On the 20th anniversary, in 2002, a theater play called “Bhopal” was staged in Canada. That's all the commemoration activities. What do you think could be the cause of this?

Union Carbide

The beginning of it all dates back to 1968. In 1968, this American company established a pesticide factory in India, which had only gained its freedom in 1947. The factory was first set up in Bombay and the company was named UCIL (Union Carbide Indian Limited). The company was 50.9% owned by UCC (Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation) and 49.1% by the Government of India and state banks. The establishment of this factory was based on the Government of India's policy of industrialization and preservation of foreign exchange reserves. These moves were launched as the Green Revolution to the people of India.

The Green Revolution is an idea developed by Norman Borlaug to address the possibility of famine on Earth. Norman Borlaug is an American agricultural scientist born in Iowa and educated in Minnesota. After working at DuPont chemical company for 2 years, he developed high-yielding and disease-resistant wheat varieties in a program supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. Throughout his life he worked very closely with the US Government, the United Nations and various international organizations.

Let us also learn a little about the pioneer of the Green Revolution in India. M.S. Swaminathan was an agricultural scientist known as the “Father of the Green Revolution” in India; he was educated at the universities of Kerala, Madras and Cambridge, worked at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute and various government agencies, and was a member of the Rajya Sabha from 2007 to 2013. After his studies, he spent time in the USA and the Netherlands. He conducted research at institutions like the University of Wisconsin and Wageningen Agricultural University.

According to one source, UCIL was there even before India declared its independence. So it was a company that had been in India since 1934. Unfortunately, I cannot state this date precisely as companies erase dates they don't like even from their own records, but what is known is that the factory in Bombay (Mumbai) was moved to Bhopal in 1968.

Bhopal, the capital of the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh (MP), was a beautiful and historic city, but unfortunately a poor state by Indian standards. The Indian National Congress Party was in power in MP and Arjun Singh was the state president in 1984. Singh played an important role in moving the agricultural office of Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) from Bombay to Bhopal in 1968. His idea was to help the development of Madhya Pradesh, but it did not work out that way.

In 1969, the UCIL Bhopal plant was built as a formulation plant. Here the organic compound Carbaryl, known by its trade name SEVIN, was produced. Carbaryl was an insecticide. Discovered 10 years before the factory was built, Carbaryl revolutionized the pesticide industry. It left no residue like chlorine pesticides. Although deadly to insects, it could be metabolized and excreted as soon as it entered the body of humans and vertebrates. It was not stored in fat tissue. However, later research revealed that this Carbaryl compound suppresses the enzyme cholinesterase in humans, which can lead to cancer. The European Union strongly opposed this and banned its use. However, the compound is still used in the US.

SEVIN's Technical Concentrate was shipped from the United States to India and the mixing and grinding was done in Bhopal. To produce this pesticide, the methyl isocyanate (MIC) molecule was used to produce many different pesticides. Thus the production of Sevin pesticide started in 1980. MIC, also used in tires and adhesives, was extremely toxic to humans and was produced in an extremely risky way. There was no antidote or cure for this horrible pesticide, and it was close to spreading like a thick blanket over people.

Actually, you know, these kinds of disasters don't come all at once. Small deficiencies, malfunctions, accumulate and are ignored. And then disaster strikes all of a sudden. Not like that, for those who had their eyes and ears open, the footsteps of the disaster could be heard eight years ago. If these voices had been heeded, the disaster would perhaps have turned from a disaster into a minor accident.

Two separate unions of Bhopal workers complained about pollution and various leaks in the factory. Of course, no one paid any attention to these complaints. In 1981, one of the workers was remodeling one of the pipes through which the phosgene gas used to produce the compound called methyl isocyanate flowed. One wrong move by the worker resulted in a large amount of phosgene being sprayed on him. Although he was wearing a mask at the time, the panic of his mistake led him to another mistake. He hurriedly removed the mask from his face to intervene more easily, but this time he inhaled a lethal amount of phosgene directly. The worker died exactly 72 hours later.

This worker was Mohammad Ashraf, a friend of Rajkumar Keswani, a journalist whose fame would later spread abroad. Ashraf had warned Keswani, a journalist, of a possible MIC gas leak due to poor maintenance and safety standards. Deeply saddened by his friend's death from inhaling phosgene and worried about the future from his warnings, Keswani decided to investigate the nature of MIC gas. He discovered that MIC contains a number of other highly toxic gases, including phosgene. He had heard of this gas before. During World War 2, it was used in gas chambers to exterminate the masses. In addition, phosgene is a much heavier gas than air. So in the event of a leak, instead of rising into the atmosphere and dissipating, it would stay at ground level and the damage would be more severe.

Determined to write an article on the subject, Keswani enlisted the help of two former employees who had been fired from the factory. After about 9 months of research and writing, Keswani published a short article in Rapat, a small news magazine published in Bhopal, on September 26, 1982, warning about his findings, and his anxiety was so great that he published the same warning back to back on October 1 and October 8. And it was pleading...

Keswani's report was quoted and shared by the national newspaper, the Indian Express, and Keswani repeated his warnings in several articles published in 1983 and 1984. “Wake up, you are sitting on the slope of a volcano,” he cried to the people of Bhopal. After his warning in 1983, 18 workers were hospitalized after being exposed to toxic gas, a mixture of Chloroform, MIC (methyl isocyanate) and Hydrochloric Acid. “If you don't understand what I am saying, you will perish,” was his last article.

In October 1984, a nitrogen leak was discovered at the factory and the nitrogen tank had to be repaired. The factory was so old that even this required repairs to other pipes first. The only reason to keep this decrepit factory active had to be profit maximization. For the same reason, the managers did not see, or rather did not want to see, so many warnings.

One of the pipes to be repaired was blocked and workers pumped water into the pipe to unclog it. In the factory, where safety standards are very low and workers work uncontrolled with no inspections, the water pumped into that blocked pipe got out of control and reached the tank containing 42 tons of MIC. The encounter between MIC and water would lead to an exothermic reaction. On the night of November 2, 1984, in the half-hour between 22:30 and 23:00, the tank pressure quintupled. This pressure could be monitored on the gauges. However, two senior workers interpreted this sudden increase in pressure as an error in the gauges. But half an hour later, the workers began to show symptoms of MIC poisoning. Coughing, shortness of breath, chest pain, itchy eyes, throat and nose. Thinking that this could be due to a leak from the tanks or pipes, they started looking for a leak in the system. After 15 minutes they found the leak. However, the managers of the factory were on a tea break at the time and delayed examining the leak for 40 minutes. Meanwhile, workers were told to look for other leaks. Despite repeated warnings, the disaster continued down the road paved by indifference. In the meantime, the pressure in the MIC tank increased five and a half times, 27 times higher than normal. For various reasons, all of the measures that would have prevented this high pressure increase had been disabled.

On December 2, 1984, two years after Keswani issued his first three warnings, his predictions were correct. A chemical reaction in one of the three plants at the factory caused tons (30 tons in the first 45 minutes) of MIC gas to leak into the air. The gas remained at ground level and spread in huge clouds over the city of Bhopal, killing thousands and injuring more than half a million people. Over the next two hours, another 10 tons of MIC entered the air. The gas was not pure. It contained toxic gases such as chloroform, dichloromethane, hydrogen chloride, carbon dioxide and was much heavier than air. So the poison did not dissipate into the air, but spread over the 500,000 or so people living around the factory. The tragedy was not over yet. The factory workers had activated two alarm systems that sounded both inside and outside. The alarm, which was needed for the people to evacuate, was immediately cut off by the managers on their tea break in order not to cause unnecessary panic. This caused the disaster to grow exponentially.

At 01:00, people started to leave their homes because of a gas leak in a neighborhood called Kola, 2 km away. When the police called the factory after seeing the movement, the managers said there was nothing to worry about. However, when the movement did not stop, the police called the factory at around 02:00 and were told, “We don't know what happened, I think there is an ammonia leak.” This lie led to further deaths. Ammonia poisoning and methyl isocyanate poisoning were not comparable. People who came to the hospital because of this news were treated for ammonia poisoning. Later, when it was said that there was a phosgene leak, the hospitals tried to update the treatment accordingly, but they were desperate. Because there was no cure for MIC poisoning, but perhaps the patients could have been denied oxygen because of respiratory problems. Because when oxygen combined with MIC in the body, it caused severe damage. Some of those who died from the gas were buried in pits and thousands were burned to death. Not only people, but also animals and even trees quickly shed their leaves and died. The soil was poisoned in an instant. No one wanted to eat or drink from it. Soon there was severe starvation.

Just a month after the incident, Union Carbide CEO Warren Anderson arrived in India with a technical team. Anderson was arrested at the airport and placed under house arrest. Don't get too excited, justice would not be served. The Indian government had gone into hiding to protect Anderson from public wrath. Warren Anderson was asked to leave the country immediately. Anderson somehow hid from the public and was secretly deported.

When legal proceedings began after the incident, Judge John F. Keenan of the Southern District of New York in the US asked Carbide to send 5 to 10 million dollars in aid to Bhopal. However, Union Carbide agreed to send 5 million dollars, ensuring that this would not be interpreted as an admission of guilt. The Government of India turned down this request. According to Union Carbide, the workers were entirely to blame. It was impossible for water to leak into the MIC tank during normal maintenance. Therefore, it had to be a deliberate act by the workers.

In 1989, a 470 million dollar compensation agreement was signed between the Government of India and Union Carbide. In 1991, CEO Warren Anderson was tried for manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in prison, the maximum sentence at the time. Although Anderson was requested in writing from the US, it was already known that he would not be released. Anderson never traveled to India and naturally was never caught and sentenced.

In 1985, Keswani received the B. D. Goenka Award for Excellence in Journalism and regretted that his warnings had gone unheeded.

“I may be the first person to receive such a magnificent award for journalistic failure.”

Although he did everything he could and his warnings were ignored by those responsible, Keswani was badly affected by the disaster. He knew that if his warnings had been heeded, this terrible tragedy could have been prevented. Despite this, Keswani went on to have a long and successful career in journalism and in 2010 received the Prem Bhatia Award for Outstanding Environmental Reporting. Sadly, Keswani lost his life to Covid19 on May 21, 2021.

After the accident, the plant was closed and Union Carbide became a subsidiary of Dow Chemical in 1999. In this way, the name was removed and the traces left behind were tried to be cleaned up. Just as Monsanto was bought by Bayer and forgotten.

Carbide CEO Warren Anderson died on September 29, 2014, at the age of 92. His family chose to hide his death from the press, while on the other side of the world people remembered him with hatred.

Today, the factory is abandoned, but leaking chemicals continue to enter the soil and water. A 2014 study found mercury in a well near the factory at a rate 500 times higher than normal. In 2009, another team detected pesticides in groundwater 3 kilometers from the factory. The area is still very toxic. Bhopal is either unheard of or forgotten, even though people still cannot go near it. Industrial disasters are not limited to Chernobyl. Don't be blinded by the invisible laws of the capitalist system that force human greed. The lessons to be learned from this event are endless...

If the mainstream media will let you...

Levent Aslan

Add Comment